( Fr- chrysocolle; Ger- Chrysokoll;

Nor- krysokoll; Rus- ![]() )

)

CHRYSOCOLLA, (Cu,Al)2H2Si2O5(OH)4·nH2O.

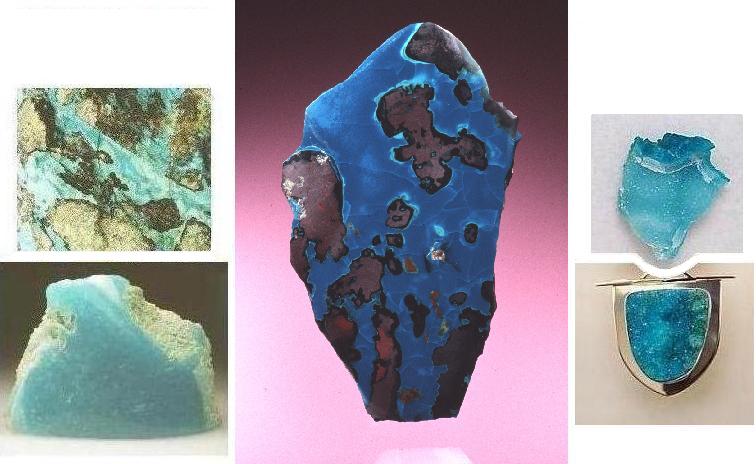

A. Chrysocolla, upper left, (width - 8.7 cm) from Inspiration Mine, Globe, Arizona. Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum. (© photo by Jeffrey A. Scovil)

B. Chrysocolla, middle, coating on cuprite (height - 4.5 cm) from the Allouez mine, Allouez, Michigan. Seaman Museum, Michigan Technological University. (© photo by John Jaszczak)

C. Drusy chrysocolla, upper right, (width - ca. 2.5 cm) from unnamed locality, Arizona. Bernardine Fine Art Jewelry, www.bernardine.com (© photo by Nancy Bernardine)

D. Chrysocolla, lower left, (width - 9.5 cm) from Silver City, Grant County, New Mexico. Canadian Museum of Nature. (© photo by Jeffrey A. Scovil)

E. Drusy chrysocolla pendant (width ca. 3.2 cm). This is actually the lower half of a pendant that includes two other stones. Bernardine Fine Art Jewelry, www.bernardine.com (© photo by Nancy Bernardine)

DESCRIPTION: Nearly all natural gemrocks

marketed as chrysocolla consist largely of SiO2 -- i.e.,

they are chrysocolla intermixed with, impregnated by, or

encrusted by quartz or chalcedony. The chrysocolla designation is

applied because

the chrysocolla content

is responsible for the color, which is the selling point for these

gemrocks. The chief difference between chrysocolla and the

silica-bearing (etc.) chrysocollas relates to their effective

hardnesses (1½ - 3½ versus ~7, respectively).

In addition, chrysocolla tends to be fragile

whereas silica-bearing (etc.) chrysocollas are not, and this is,

of course, a major consideration so far as most gemrock uses.

Nonetheless,

some massive chrysocolla per se has also been used --

albeit

only rarely -- as a gemrock (Robertson, 1981). The following

properties

are for chrysocolla per se.

Colors - diverse blue and bluish green hues

H. 3

S.G. 1.9-2.2

Light transmission - translucent to opaque

Luster - earthy, dull to vitreous

Breakage - brittle with subconchoidal

fracture

Miscellany - typically

cryptocrystalline; is decomposed by HCl. For some

people, especially collectors, it may be significant to note that

minerals such as ajoite, papagoite and shattuckite can be, and may have

been, mistakenly identified as chrysocolla (Kammerling and Fryer,

1995, p.120); anyone who feels the need to

have specimens or fashioned gemrock pieces, indicated to be

chrysocolla,

checked with regard to these possibilities should have the

identifications made by a professional mineralogist.

OTHER NAMES:

USES: Cabochons for diverse pieces of jewelry and ornaments, including figurines and carvings, some of which have been marketed as a turquoise substitutes.

OCCURRENCES: Typically as crusts, small stalactitelike, and/or botryoidal masses spatially associated with other secondary copper minerals within oxidized zones of copper deposits.

NOTEWORTHY LOCALITIES: Copper districts Congo (formerly Zaire, formerly Belgian Congo); Chile and Peru (e.g., Lily mine, near Ica); Barranca del Cobre, Chihuahua, Mexico. Also Arizona -- e.g., the Bisbee mine, Conchise County; mines of the Globe-Miami district of Gila County; the Morenci mine, Greenlee County; and the Ray mine, Pinal County. And, sporadically in copper-bearing rocks of Utah and New Mexico.

REMARKS: The designation chrysocolla is

usually attributed to Theophrastus (ca.

315 B.C.); Mitchell (1979) notes that it is "from Greek words

meaning gold and glue, originally given by the

ancients to a mineral or minerals used for soldering gold, but long

applied to various green copper minerals." Bisbeeite, a

discredited mineral name, is the name

given to chrysocolla, especially that from Arizona, in some

publications.

Pure chrysocolla is fragile and tends to break easily, especially after undergoing what is frequently called spontaneous dehydration, when exposed to the atmosphere. Although much chrysocolla is marketed as "stabilized," to date I have found nothing recorded about the "stabilization" process(es) used other than a few cryptic remarks about suggesting the use of epoxy resin .

Some chrysocolla-colored chalcedony undergoes repeatable changes when soaked in water, dried, etc., or even with changes in humidity -- i.e., its blue color becomes more intense; it appears to become less opaque; and, as one might suspect, it takes on weight, attributable to the absorbed water. Examples of this material have been recorded from Mexico (Koivula, Kammerling and Fritsch, 1992, p.59-60) and Arizona (Johnson and Koivula, 1996, p.129-130).

According to Zeitner (1985), this gemrock was

"voted the most popular American gem by

lapidaries" during the 1950s.

SIMULANTS: None that I have seen or seen described.

REFERENCES: Robertson, 1981; Zeitner, 1985.

R. V. Dietrich © 2015

Last

update: 16 Juley 2005

web page created by Emmett Mason