(Singular nouns: Fr-os; Ger-Bein; Nor-ben/bein/knokkle?; Rus- костб)

Last update: 22 June 2016

A. Bones (length - 18.8 cm).

Set of rib bones (species unidentified) fashioned to play like

spoons for adding

rhythm to, for

example, square dancing music. George B.

Dietrich, original owner/player. (© photo by Dick

Dietrich)

DESCRIPTION:

Statements to the effect that bones are bone, antlers are bone, and bone is largely the mineral apatite (i.e., Ca5(PO4)3(OH)) intermixed with organic materials (e.g., collagen) though basically correct are oversimplifications. It has long been recognized that the composition, and consequently some of the characteristics and properties, of bones are not all the same: They differ from species to species; from one individual to another of the same species; from bone to bone within individuals; and even for the same bone from time to time --e.g., with an individual's age; ... The environment and availability of food where the animal lived are major, but not the only, controls.

Over the years, as investigators have gained access to more sophisticated analytical instruments, information about the composition of bone(s) has increased greatly. The following quotations about the composition of human bone provides insight so far as what is or can be learned currently about any given bone: "Tissues typical of bones have woven, lamellar, and Haversian textures with mineral distribution and content that varies with tissue age, with nutrition, ..." [Although] "The bio-deposits conform crystal chemically most closely to the mineral species hydroxylapatite in the ideal formula Ca5(PO4)3(OH) [,] ... The following formula is a more appropriate presentation:

The brackets [in the formula] indicate vacancies in some lattice sites of the solid, which are necessary in order to achieve a charge-balanced solid phase. ... This complicated chemical solid can be described as follows: bioapatite [my emphasis] is predominantly a calcium phosphate mineral most closely resembling the species hydroxylapatite but usually contains many elements and molecular species other than calcium and phosphate that probably contribute to its physical attributes and reactivity, and should be part of any identification." (Skinner, 2004).

The complexities and diversity of bones' compositions notwithstanding, the following properties obtain for hard bone -- i.e., bone from which virtually all or most of the originally present organic material has been removed. They are listed to aid anyone who is using only macroscopic observations to identify bone or to distinguish it from other natural and artificial materials that resemble or are questionably reported to be bone.

Colors - typically off-white, grayish or tan.

Texture - Haversian canals, which permeate most bones, can be seen with one's naked eye or by using a hand lens: In transverse sections, they appear as small subcircular holes (dots or short dashes); in longitudinal sections, they appear as roughly parallel linear areas (flecks), which in some specimens appear “dirty.”

H.(effective hardness) 5; [2½ - Webster, 1948-1949]

S.G. 2.30 - 2.57; [1.95 - 2.20 - Webster, 1948-1949], but several measurements on "whole bones" have given much lower values -- as low as 1.08 -- apparently because of the porosity of the measures specimens.

Light transmission - semitranslucent to opaque

Luster - dull to waxy

Breakage - irregular; long bones tend to be splintery.

Miscellaneous - Hard bone is relatively porous; the originally present organic material comprises up to 30 per cent of some bones (Hoppe, Koch and Furutani, 2003). Antlers are typically coarser and exhibit more spongy porous interiors than most other bones.

Some people incorrectly equate antlers and horns. Differences include the following: antlers are predominantly bone whereas horn is largely keratin; antlers are shed annually, horns are not shed naturally; antlers are typically branched, horns are not. “In-betweeners,” however, exist – the horns of the Pronghorn (Antilocarpra americana (Ord, 1815)) are an example: its horns, which consist of keratin growing on a bony core, are shed annually and, on males, are commonly branched.

OTHER NAMES: Bone has no other name applied to it so far as the subject of this presentation. This notwithstanding, bone should not be confused with Bone (Bony or Osseous) amber or Bone turquoise (Odontolite) – see Amber and Turquoise entries in GEMROCKS file and notes re odontolite in Ivory and Teeth entries in this folder. Antler, on the other hand, has frequently been given names such as stag horn and hart(s) horn, which, as just mentioned, are misleading in that antler is bone, not horn.

USES: Items described and illustrated by MacGregor (1985) as representing “[t]he technology of skeletal materials since the Roman period” include the following (with those made of Antlers as well as other bones preceded by an asterisk): *amulets, apple corers (cheese scoops?), *arrowheads, beads, *bobbins, *bows (e.g., parts for both composite and cross bows), *bracelets, brushes (i.e., the frames to hold the filaments), buckles, buttons, *cases (e.g., for combs and mirrors), casket panels, *clamps, coin balances, *combs, *cutlery (spoons and knives), dice, *fastening pins, gaming pieces (discs and chess pieces), *hammers, *handles (for cutlery, daggers, swords and tools), hinges, ice skates, “motif pieces” (e.g., for casting ornaments or prodding repoussé effects), *mountings (e.g., decorative and/or inscribed for caskets and furniture), *plane stock, *points and cleavers, scabbard chapes and slides, scoops, seal matrices, sledge runners, spectacle frames, *stamps (for pottery and leather), strap ends (e.g., for belts), *string instrument parts (e.g., tuning pins), styluses, tablets for writing, *textile-working equipment (e.g., combs, spindles and whorls), toggles, toilet sets, and *tools for tilling (e.g., clod-breakers, hoes and rakes). In addition, MacGregor specifies the animal and the name of its bone, bones and/or parts of its antlers (if any) are used for the different items; this specificity reflects, of course, the fact that each bone in an animal differs from its other bones because of its function.

Other things recorded as fashioned from bone and/or antlers include awls, cutting boards, hoes, pickaxes, scrapers, shovels, diverse toys (e.g., buffalo-rib sleds used by Lakota Sioux children) and even paintbrushes -- the porous ends were used to soak up paint and used to paint things like hides (NPS, nd) -- and several other uses are described and illustrated by Halstead & Middleton (1972). A use to which my attention was recently (September 2011) was directed is exemplified by a carved vomiting stick that was carved from manatee bone (Poole, 2011, p.69); it seems likely that bones, many of which were not carved, of several other animals have found similar use. Also, Bergman, Azoury and Seeden (2012) record the pre-historic Ahmarians "using hammers made of organic materials like deer antler" to shape flint into their projectile points, knives and scrapers.

Present-day examples of uses follow:

Carvings - beads, carvings per se (e.g., Figure B), carvings in relief on bone surfaces (Figure C), antler carvings and scrimshaw (Figure D), statuettes and miscellaneous decorations.

B. Bone. Whalebone carving of an owl (greatest dimension ~28 cm), carved by Joanassie Jaw of the Cape Dorset Community, Nunavuto. (© photo courtesy Eskimo Art Gallery, www.eskimoart.com).

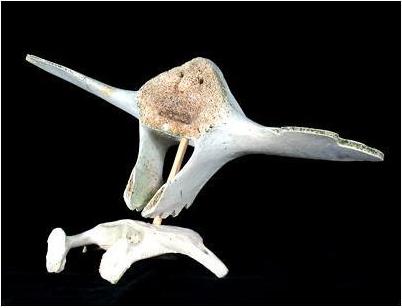

C. Bone. Cribbage board, carved by Alaskan Master Artist Mr. B. Merry from a fossil walrus (Odobenus rosmarus (Linnaeus, 1758)) jawbone found buried in sand and clay. (© photo from www.kasilofseafoods.com).

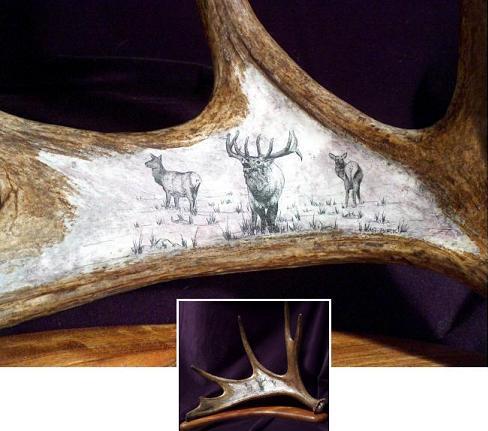

D2. Antler. Painting on male moose [Alces alces (Linnaeus, 1758)] palmate antler that is on

a wall of

the Cut River Inn restaurant, Michigan. I was told that the

painting was by a John McGraw of Beaverton, Michigan. (© photo by Dick

Dietrich)

Jewelry - beads, some of

which are carved and/or dyed,

body ornaments (e.g., a

four-strand, 19-inch long New Guinea body

ornament fashioned from the leg bones of birds),

chokers and pendants of bone cabochons or carved bone (Figure E),

earrings made of carved

bone tubes and diverse

pieces of

jewelry in which bone is combined with other

gemstones (e.g.,

ivory and/or turquoise). Especially noteworthy are the necklaces,

bracelets and earrings marketed rather widely as Mah-Jongg

jewelry; the foci are bone tiles that feature diverse decorative

patters that are most commonly black and/or red. Particularly

interesting pieces --

e.g., earrings and pendants --

have been fashioned to feature

fish ear bones (see Figure F). Some bone carved to resemble feathers

have been marketed as, for example, earrings; some of these have

been painted so they look much like the feathers of known species --

e.g., those of bluejays, eagles, and snowy owls.

E. Bone. "Dew Eagle" pendant (height - 5 cm) carved from water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) bone in Vietnam or China. (© photo Chichester Inc., from www.chichesterinc.com)

F. Bone. Baroque-shaped fish ear bone (25 x 14 x 12 mm) from a South American silver croaker (Plagioscion squamosissimus (Heckel, 1840)). These bones are referred to as otoliths (from the Ancient Greek oto [ear] and lithos [stone]). (© photo Stefanos Karampelas, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece)

Musical “instruments” - 1. Flutes -- “The pneumatic limb bones (particularly ulnae and tibiae) of large birds were ... favoured, their long, thin-walled hollow shafts suiting them admirably for this purpose” (MacGregor, 1985, p. 150). Twelve plates of photographs of bone flutes -- one (Plate 1,l ), made from a bear's lower jawbone, that was found at the well-known Potočka zijalka excavations in Slovenia -- are given by Brade (1975, p.13). The discovery of a ~ 40,000-year old bone flute in a German cave was recently reported by Owen (2009). That flute is said to have been "Fashioned from a griffon vulture's wing bone ... [,] maybe the world's oldest [musical] instrument, ... [and it is added that its exostemce] bolsters the argument that music helped modern human's bond -- to the detriment of competing presumably music-less Neanderthals." (op. cit.). Additional information and photograph of the flute constitute the release. ).

2. Percussion -- examples are rib bones from horses or cattle that are played like spoons (see Figure A), jaw bones of asses including their loose teeth used as rattles or shakers (see Figure G) and drums such as those made of pig bladder stretched tightly over halved/sawn human sculls (Halstead & Middleton, 1972, p.65). [and]

3. Wind “chimes” -- albeit only musical instruments in a broad sense.

Tools and weapons - cutlery handles, hunting knife and Gaelic sgian dubh ("black dagger") handles, pocket and hunting and skinning knife sheaths, scrapers and arrowheads.

Miscellany - parts of facetious biomorphs, buttons, coffers, buckles, door knobs (some of which are carved), jewelry boxes (see following paragraph), pipes, shoe horns and as veneers (e.g., on “barrels” of binoculars). Also, on a larger scale -- antlers have been fashioned into such things as candle holders, chandeliers, handles for baskets, lamps, pool cue racks and sconces as well as the relatively common coat and hat racks. In addition, a former use seems noteworthy from the standpoint that it may serve as a “new method” for some craftsmen: Vikings cut forms on reindeer antler pedicles and used them as molds for casting such things as brooches (MacGregor, 1985, p. 195).

Some of the replicas of the small boxes, referred to as Mughal boxes, are covered wholly or in part by bone. These boxes are so-named because they are fashioned to resemble, at least shape-wise, the boxes that were used to store jewelry during he Mughal Dynasty (1526-1756) of India.

OCCURRENCES & LOCALITIES: Bones of just about any animal (including birds) have been used for fashioning decorative and/or functional items. Those of particular note have come from buffaloes (bison), camels, cattle, sheep, whales and humans. Although bones occur virtually everywhere, many bones currently used for fashioning objects, especially those for the marketplace, are chosen from “collections” that are so-to-speak controlled, albeit usually considered waste, by butchers, skinners and tanners. A large proportion of the antlers that are so-used have been shed. Most of those that have been used for fashioning decorative objects have come from deer (including reindeer [=caribou]) and moose (elk).

REMARKS: The word bone is generally agreed to have come from the Old English bān via Middle English bon. Antler appears to stem back to the Vulgar Latin anteoculāre (Latin, ante oculāris -- in front of the eye). Derivation of the designation osteolith, sometimes used as a synonym for bone-phosphate, is also of interest from the standpoint of etymology: It is from the Greek ὸστέον, bone and λιθος, stone.

Bone is sometimes steep...[ed in brine for several days; simmer[ed] in hot water for about 6 hours to remove fatty matter" (Webster, 1975, p. 526) before being fashioned by carving etc. Bone, including antler, has been dyed or stained for various uses.

From time immemorial, certain bones (including antlers) have found relatively wide use. Those that on the basis of their shapes were found “to serve the purpose” are examples. Fresh bones usually require degreasing before use. Long bones have a “grain” that must be considered when fashioning objects from them. Soaking tends to reduce the stiffness of some bones and in some cases even make them easier to cut. MacGregor (1985, p.63-65) describes and discusses experiments relating to promoting such softening in diverse solutions, such as vinegar and sour milk. Bone has been dyed for some uses -- see, for example, Mother of...(n.d., "bone material").

Whenever I think about bones, one thing that comes to mind is jawbone of an ass – see in the Bible, Old Testament, Judges 15:16, "With the jawbone of an ass . . . have I slain a thousand men." Aesthetic uses of bone, however, pre-date at least Sampson's use of it as a weapon by many thousands of years: Examples are the use as beads made from kangaroo bone in Australia dated as 13,000 to 10,000 B.C. and a “necklace of head-shaped ibex beads made from ibex bone with a bison head backpiece ...[from] late French Magdalenian culture. [And] Found at La Bastide, France, and dated between 11,000 and 10,000 B.C. [-- a necklace that] archaeologists believe ... was used to evoke magical powers sympathetic to hunting. By wearing beads made from the bone of the prey and shaped in its likeness, the hunter hoped to increase his chances for success.”(Dubin, 1987, p. 25).

An especially interesting Neolithic (5,000-year-old) whalebone figurine, carved to depict a human "form" and referred to as the "Mysterious 'Buddo' ..." was discovered in the 1850s at the Skara Brae archaeological site in the Orkney Islands. It recently became newsworthy because it was found after having been "lost" for more than 150 years; a description and photographs of it are given in Metcalfe (2016).

Oracle bones is the designation frequently given “bones used for divination by the Chinese during the Shang dynasty (traditionally c.1766 B.C.–c.1122 B.C.). Along with contemporary inscriptions on bronze vessels, these records of divination, which were incised on the shoulder blade[bone]s of animals (mainly oxen) and on turtle shells, contain the earliest form of Chinese writing. In addition to being an important source for understanding the development of written Chinese, they tell a great deal about Shang society. Questions asked by the diviners concerned such matters as sacrifices, weather, war, hunting, travel, and luck. The bones were heated to produce cracks from which 'yes' or 'no' answers were somehow derived [construed(?)]. A small number of oracle bones have the answer and the eventual outcome inscribed. Discovered in the ruins of the Shang capital of Anyang in the late 19th cent., they were first sold as so-called dragon bones to be ground up for use in Chinese medicinal compounds and only received the attention of scholars in the 1920s.” (Columbia Encyclopedia, 2001-2005).

Buddhist mala, which are beads fashioned from bones of lamas, were used as prayer beads. Mongolians used human skull caps as cups and drilled human femurs to produce what are now marketed as "antique Mongolian Buddhist thighbone trumpets." Tibetans of the Black Hat magician sect made prayer beads from human bone; apparently, as “objects of human bone [they] were meant to impress upon the devotee the transient nature or human existence.” (Dubin, 1987, p.82).

Some extremely complex/intricate models of ships have been made from bone; several of them were made, in some cases under commissions, by prisoners of war while they were being held in prison camps. Photographs of four of them are given by Ritchie (1950, p. 124-127), who also records the following story about yet another one:

"The most romantic commission ... was placed by some English ladies. They had been

captured at sea by the famous French privateer Surcouf. French Privateers at that time

had a bad reputation; the fair captives expected a fate worse than death, then death itself.

However, Surcouf treated them with the utmost chivalry, and returned them, unharmed, to

British hands. As a reward for what the privateer had done, or as M. Bazin puts it, 'for

what he had not done,' the ladies commissioned a bone ship as a present for the French

captain, and had it rigged with strands of their hair so that their gallant captor would always

have something to remind him of his former prisoners." (ibid., p.133)

"Stem cells play a key role in the deer's remarkable ability to grow new antlers, according to research. The deer is unique among mammals in being able to regenerate a complete body part - in this case a set of bone antlers covered in velvety skin. Experts at the Royal Veterinary College hope the work could one day lead to new ways to repair damaged human tissues. Details were outlined in an edition of the BBC TV program Super Vets, which was screened on 12 January. Professor Joanna Price of the Royal Veterinary College said: 'The regeneration of antlers remains one of the mysteries of biology but we are moving some way to understanding the mechanisms involved. Antlers provide us with a unique natural model that can help us understand the basic process of regeneration although we are still a long way from being able to apply this work to humans.'" (BBC NEWS, 2006).

In a lighter vein, the red deer stag with the great rack of antlers that is associated in many people's minds with the Hartford Insurance Company is one of the most widely reconized symbols in the world of advertizing. This stag is based on the painting "Monarch at the Glen" (dated 1851) by the famous English painter and sculptor Sir Edwin Landseer (1802-1873). Although the Hartford company's use of the stag dates to 1861, the background of the original painting was modified at least two times before 1875 when it was resolved to the one that is used today. This symbol, by the way, probably gained its largest audience when, during the 1970s, the stag was so-to-speak incarnated by Lawrence, an elk that was dubbed "the Hartford stag"; Lawrence wandered around through all sorts of settings as the foci of of television commercials for the company. (see Barlow, 2006)

For those interested in the history of the use of bone, several interesting anecdotes and illustrations (black and white photographs), I recommend two references: Ritchie (1975) and MacGregor (1985).

SIMULANTS: Particularly for collectors of ancient bone tools (etc.), bones with shapes such as those of the "Pseudo-tools made by hyaena digestive juices and gnawing" (Halstead & Middleton, 1972, p.57), though not simulants, seem worth mentioning. True simulants follow:

Ivory - This is a case where ivory pieces have been misidentified, NOT purposely misrepresented as bone, which is be ridiculous. - [Textures marked by differences in distributions of color patterns suffice to distinguish ivory from bone - see descriptions of each.].

***Plastics - Plastics, otherwise unidentified (at least so far as I have been able to determine), have been used for such things as jack-knife casings that resemble bone. - [Close examination suffices because the plastic lacks Haversian canals and other characteristic textures of bone.].

***Resins - Handles of Gaelic sgian dubh ("black dagger") have been made of resin. - [Close examination suffices.].

***Reconstituted bone - Finely powdered bone that has been sintered has been used, usually molded, to fashion figurines etc., but -- I suspect -- usually to resemble ivory rather than bone. - [Close examination suffices.].

REPLICAS: Many replicas of animals, including humans, have been produced for such diverse things as teaching aids and ostentatious displays. Most are made from resin plus or minus additives such as crushed bone; some are subsequently weathered before being marketed. One of the finest replicas I have seen was a collection piece hunter's knife with a ceramic handle featuring a stag with a ten-point rack and its doe mate. Some so-to-speak replicas -- most are what I would characterize as cartoon-like moose with full racks -- have been made for use as Christmas tree ornaments, footrests, mantel pieces for holiday festivities and slippers. Rather life-like Bas-reliefs of elks are featured on many ceramic steins and also on some rather interesting jewelry boxes -- interesting because the material from which they are made, called "incolay stone," is described in advertisements as a "complex combination of ... [apparently crushed and sintered] quartz, onyx and carnelian." Essentially two-dimensional representatives of these same animals are also marketed: Examples are engraved glass steins, flat metal wall hangings, pillow covers and clothing (e.g., nightshirts and T-shirts).

DESCRIPTION:

Statements to the effect that bones are bone, antlers are bone, and bone is largely the mineral apatite (i.e., Ca5(PO4)3(OH)) intermixed with organic materials (e.g., collagen) though basically correct are oversimplifications. It has long been recognized that the composition, and consequently some of the characteristics and properties, of bones are not all the same: They differ from species to species; from one individual to another of the same species; from bone to bone within individuals; and even for the same bone from time to time --e.g., with an individual's age; ... The environment and availability of food where the animal lived are major, but not the only, controls.

Over the years, as investigators have gained access to more sophisticated analytical instruments, information about the composition of bone(s) has increased greatly. The following quotations about the composition of human bone provides insight so far as what is or can be learned currently about any given bone: "Tissues typical of bones have woven, lamellar, and Haversian textures with mineral distribution and content that varies with tissue age, with nutrition, ..." [Although] "The bio-deposits conform crystal chemically most closely to the mineral species hydroxylapatite in the ideal formula Ca5(PO4)3(OH) [,] ... The following formula is a more appropriate presentation:

Ca,Na,Mg[ ])10(PO4,HPO4,CO3)6(OH,F,Cl,CO3,O[

])2

The brackets [in the formula] indicate vacancies in some lattice sites of the solid, which are necessary in order to achieve a charge-balanced solid phase. ... This complicated chemical solid can be described as follows: bioapatite [my emphasis] is predominantly a calcium phosphate mineral most closely resembling the species hydroxylapatite but usually contains many elements and molecular species other than calcium and phosphate that probably contribute to its physical attributes and reactivity, and should be part of any identification." (Skinner, 2004).

The complexities and diversity of bones' compositions notwithstanding, the following properties obtain for hard bone -- i.e., bone from which virtually all or most of the originally present organic material has been removed. They are listed to aid anyone who is using only macroscopic observations to identify bone or to distinguish it from other natural and artificial materials that resemble or are questionably reported to be bone.

Colors - typically off-white, grayish or tan.

Texture - Haversian canals, which permeate most bones, can be seen with one's naked eye or by using a hand lens: In transverse sections, they appear as small subcircular holes (dots or short dashes); in longitudinal sections, they appear as roughly parallel linear areas (flecks), which in some specimens appear “dirty.”

H.(effective hardness) 5; [2½ - Webster, 1948-1949]

S.G. 2.30 - 2.57; [1.95 - 2.20 - Webster, 1948-1949], but several measurements on "whole bones" have given much lower values -- as low as 1.08 -- apparently because of the porosity of the measures specimens.

Light transmission - semitranslucent to opaque

Luster - dull to waxy

Breakage - irregular; long bones tend to be splintery.

Miscellaneous - Hard bone is relatively porous; the originally present organic material comprises up to 30 per cent of some bones (Hoppe, Koch and Furutani, 2003). Antlers are typically coarser and exhibit more spongy porous interiors than most other bones.

Some people incorrectly equate antlers and horns. Differences include the following: antlers are predominantly bone whereas horn is largely keratin; antlers are shed annually, horns are not shed naturally; antlers are typically branched, horns are not. “In-betweeners,” however, exist – the horns of the Pronghorn (Antilocarpra americana (Ord, 1815)) are an example: its horns, which consist of keratin growing on a bony core, are shed annually and, on males, are commonly branched.

OTHER NAMES: Bone has no other name applied to it so far as the subject of this presentation. This notwithstanding, bone should not be confused with Bone (Bony or Osseous) amber or Bone turquoise (Odontolite) – see Amber and Turquoise entries in GEMROCKS file and notes re odontolite in Ivory and Teeth entries in this folder. Antler, on the other hand, has frequently been given names such as stag horn and hart(s) horn, which, as just mentioned, are misleading in that antler is bone, not horn.

USES: Items described and illustrated by MacGregor (1985) as representing “[t]he technology of skeletal materials since the Roman period” include the following (with those made of Antlers as well as other bones preceded by an asterisk): *amulets, apple corers (cheese scoops?), *arrowheads, beads, *bobbins, *bows (e.g., parts for both composite and cross bows), *bracelets, brushes (i.e., the frames to hold the filaments), buckles, buttons, *cases (e.g., for combs and mirrors), casket panels, *clamps, coin balances, *combs, *cutlery (spoons and knives), dice, *fastening pins, gaming pieces (discs and chess pieces), *hammers, *handles (for cutlery, daggers, swords and tools), hinges, ice skates, “motif pieces” (e.g., for casting ornaments or prodding repoussé effects), *mountings (e.g., decorative and/or inscribed for caskets and furniture), *plane stock, *points and cleavers, scabbard chapes and slides, scoops, seal matrices, sledge runners, spectacle frames, *stamps (for pottery and leather), strap ends (e.g., for belts), *string instrument parts (e.g., tuning pins), styluses, tablets for writing, *textile-working equipment (e.g., combs, spindles and whorls), toggles, toilet sets, and *tools for tilling (e.g., clod-breakers, hoes and rakes). In addition, MacGregor specifies the animal and the name of its bone, bones and/or parts of its antlers (if any) are used for the different items; this specificity reflects, of course, the fact that each bone in an animal differs from its other bones because of its function.

Other things recorded as fashioned from bone and/or antlers include awls, cutting boards, hoes, pickaxes, scrapers, shovels, diverse toys (e.g., buffalo-rib sleds used by Lakota Sioux children) and even paintbrushes -- the porous ends were used to soak up paint and used to paint things like hides (NPS, nd) -- and several other uses are described and illustrated by Halstead & Middleton (1972). A use to which my attention was recently (September 2011) was directed is exemplified by a carved vomiting stick that was carved from manatee bone (Poole, 2011, p.69); it seems likely that bones, many of which were not carved, of several other animals have found similar use. Also, Bergman, Azoury and Seeden (2012) record the pre-historic Ahmarians "using hammers made of organic materials like deer antler" to shape flint into their projectile points, knives and scrapers.

Present-day examples of uses follow:

Carvings - beads, carvings per se (e.g., Figure B), carvings in relief on bone surfaces (Figure C), antler carvings and scrimshaw (Figure D), statuettes and miscellaneous decorations.

B. Bone. Whalebone carving of an owl (greatest dimension ~28 cm), carved by Joanassie Jaw of the Cape Dorset Community, Nunavuto. (© photo courtesy Eskimo Art Gallery, www.eskimoart.com).

C. Bone. Cribbage board, carved by Alaskan Master Artist Mr. B. Merry from a fossil walrus (Odobenus rosmarus (Linnaeus, 1758)) jawbone found buried in sand and clay. (© photo from www.kasilofseafoods.com).

D1. Antler.

"Bugling bull elk

with two cows scrimshawed on naturally shed moose [Alces alces (Linnaeus, 1758)] antler."

(© photo courtesy of Alaska

Antler Works, from www.alaskaantlerworks.com).

E. Bone. "Dew Eagle" pendant (height - 5 cm) carved from water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) bone in Vietnam or China. (© photo Chichester Inc., from www.chichesterinc.com)

F. Bone. Baroque-shaped fish ear bone (25 x 14 x 12 mm) from a South American silver croaker (Plagioscion squamosissimus (Heckel, 1840)). These bones are referred to as otoliths (from the Ancient Greek oto [ear] and lithos [stone]). (© photo Stefanos Karampelas, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece)

Musical “instruments” - 1. Flutes -- “The pneumatic limb bones (particularly ulnae and tibiae) of large birds were ... favoured, their long, thin-walled hollow shafts suiting them admirably for this purpose” (MacGregor, 1985, p. 150). Twelve plates of photographs of bone flutes -- one (Plate 1,l ), made from a bear's lower jawbone, that was found at the well-known Potočka zijalka excavations in Slovenia -- are given by Brade (1975, p.13). The discovery of a ~ 40,000-year old bone flute in a German cave was recently reported by Owen (2009). That flute is said to have been "Fashioned from a griffon vulture's wing bone ... [,] maybe the world's oldest [musical] instrument, ... [and it is added that its exostemce] bolsters the argument that music helped modern human's bond -- to the detriment of competing presumably music-less Neanderthals." (op. cit.). Additional information and photograph of the flute constitute the release. ).

2. Percussion -- examples are rib bones from horses or cattle that are played like spoons (see Figure A), jaw bones of asses including their loose teeth used as rattles or shakers (see Figure G) and drums such as those made of pig bladder stretched tightly over halved/sawn human sculls (Halstead & Middleton, 1972, p.65). [and]

3. Wind “chimes” -- albeit only musical instruments in a broad sense.

Tools and weapons - cutlery handles, hunting knife and Gaelic sgian dubh ("black dagger") handles, pocket and hunting and skinning knife sheaths, scrapers and arrowheads.

Miscellany - parts of facetious biomorphs, buttons, coffers, buckles, door knobs (some of which are carved), jewelry boxes (see following paragraph), pipes, shoe horns and as veneers (e.g., on “barrels” of binoculars). Also, on a larger scale -- antlers have been fashioned into such things as candle holders, chandeliers, handles for baskets, lamps, pool cue racks and sconces as well as the relatively common coat and hat racks. In addition, a former use seems noteworthy from the standpoint that it may serve as a “new method” for some craftsmen: Vikings cut forms on reindeer antler pedicles and used them as molds for casting such things as brooches (MacGregor, 1985, p. 195).

Some of the replicas of the small boxes, referred to as Mughal boxes, are covered wholly or in part by bone. These boxes are so-named because they are fashioned to resemble, at least shape-wise, the boxes that were used to store jewelry during he Mughal Dynasty (1526-1756) of India.

OCCURRENCES & LOCALITIES: Bones of just about any animal (including birds) have been used for fashioning decorative and/or functional items. Those of particular note have come from buffaloes (bison), camels, cattle, sheep, whales and humans. Although bones occur virtually everywhere, many bones currently used for fashioning objects, especially those for the marketplace, are chosen from “collections” that are so-to-speak controlled, albeit usually considered waste, by butchers, skinners and tanners. A large proportion of the antlers that are so-used have been shed. Most of those that have been used for fashioning decorative objects have come from deer (including reindeer [=caribou]) and moose (elk).

REMARKS: The word bone is generally agreed to have come from the Old English bān via Middle English bon. Antler appears to stem back to the Vulgar Latin anteoculāre (Latin, ante oculāris -- in front of the eye). Derivation of the designation osteolith, sometimes used as a synonym for bone-phosphate, is also of interest from the standpoint of etymology: It is from the Greek ὸστέον, bone and λιθος, stone.

Bone is sometimes steep...[ed in brine for several days; simmer[ed] in hot water for about 6 hours to remove fatty matter" (Webster, 1975, p. 526) before being fashioned by carving etc. Bone, including antler, has been dyed or stained for various uses.

From time immemorial, certain bones (including antlers) have found relatively wide use. Those that on the basis of their shapes were found “to serve the purpose” are examples. Fresh bones usually require degreasing before use. Long bones have a “grain” that must be considered when fashioning objects from them. Soaking tends to reduce the stiffness of some bones and in some cases even make them easier to cut. MacGregor (1985, p.63-65) describes and discusses experiments relating to promoting such softening in diverse solutions, such as vinegar and sour milk. Bone has been dyed for some uses -- see, for example, Mother of...(n.d., "bone material").

Whenever I think about bones, one thing that comes to mind is jawbone of an ass – see in the Bible, Old Testament, Judges 15:16, "With the jawbone of an ass . . . have I slain a thousand men." Aesthetic uses of bone, however, pre-date at least Sampson's use of it as a weapon by many thousands of years: Examples are the use as beads made from kangaroo bone in Australia dated as 13,000 to 10,000 B.C. and a “necklace of head-shaped ibex beads made from ibex bone with a bison head backpiece ...[from] late French Magdalenian culture. [And] Found at La Bastide, France, and dated between 11,000 and 10,000 B.C. [-- a necklace that] archaeologists believe ... was used to evoke magical powers sympathetic to hunting. By wearing beads made from the bone of the prey and shaped in its likeness, the hunter hoped to increase his chances for success.”(Dubin, 1987, p. 25).

G. Bone. Cataloged as "Jawbone of an

ass" (Equus asinus

Linnaeus, 1758) -- greatest

dimension - 42 cm -- complete

with teeth, from Cuba. Wayne Moore

Collection. Dr. Moore

was presented this piece when he left Cuba in 1958. Oil geologist

colleagues, who had seen how intrigued he was with the use of one of

these as

a percussion instrument by a Latin music player in a nightclub in

Havana, saw it as an appropriate

going-away gift.

Subsequently, it has been on display in Wayne’s office and, since

retirement, in his home. (© photo by Dick

Dietrich)

An especially interesting Neolithic (5,000-year-old) whalebone figurine, carved to depict a human "form" and referred to as the "Mysterious 'Buddo' ..." was discovered in the 1850s at the Skara Brae archaeological site in the Orkney Islands. It recently became newsworthy because it was found after having been "lost" for more than 150 years; a description and photographs of it are given in Metcalfe (2016).

Oracle bones is the designation frequently given “bones used for divination by the Chinese during the Shang dynasty (traditionally c.1766 B.C.–c.1122 B.C.). Along with contemporary inscriptions on bronze vessels, these records of divination, which were incised on the shoulder blade[bone]s of animals (mainly oxen) and on turtle shells, contain the earliest form of Chinese writing. In addition to being an important source for understanding the development of written Chinese, they tell a great deal about Shang society. Questions asked by the diviners concerned such matters as sacrifices, weather, war, hunting, travel, and luck. The bones were heated to produce cracks from which 'yes' or 'no' answers were somehow derived [construed(?)]. A small number of oracle bones have the answer and the eventual outcome inscribed. Discovered in the ruins of the Shang capital of Anyang in the late 19th cent., they were first sold as so-called dragon bones to be ground up for use in Chinese medicinal compounds and only received the attention of scholars in the 1920s.” (Columbia Encyclopedia, 2001-2005).

Buddhist mala, which are beads fashioned from bones of lamas, were used as prayer beads. Mongolians used human skull caps as cups and drilled human femurs to produce what are now marketed as "antique Mongolian Buddhist thighbone trumpets." Tibetans of the Black Hat magician sect made prayer beads from human bone; apparently, as “objects of human bone [they] were meant to impress upon the devotee the transient nature or human existence.” (Dubin, 1987, p.82).

Some extremely complex/intricate models of ships have been made from bone; several of them were made, in some cases under commissions, by prisoners of war while they were being held in prison camps. Photographs of four of them are given by Ritchie (1950, p. 124-127), who also records the following story about yet another one:

"The most romantic commission ... was placed by some English ladies. They had been

captured at sea by the famous French privateer Surcouf. French Privateers at that time

had a bad reputation; the fair captives expected a fate worse than death, then death itself.

However, Surcouf treated them with the utmost chivalry, and returned them, unharmed, to

British hands. As a reward for what the privateer had done, or as M. Bazin puts it, 'for

what he had not done,' the ladies commissioned a bone ship as a present for the French

captain, and had it rigged with strands of their hair so that their gallant captor would always

have something to remind him of his former prisoners." (ibid., p.133)

"Stem cells play a key role in the deer's remarkable ability to grow new antlers, according to research. The deer is unique among mammals in being able to regenerate a complete body part - in this case a set of bone antlers covered in velvety skin. Experts at the Royal Veterinary College hope the work could one day lead to new ways to repair damaged human tissues. Details were outlined in an edition of the BBC TV program Super Vets, which was screened on 12 January. Professor Joanna Price of the Royal Veterinary College said: 'The regeneration of antlers remains one of the mysteries of biology but we are moving some way to understanding the mechanisms involved. Antlers provide us with a unique natural model that can help us understand the basic process of regeneration although we are still a long way from being able to apply this work to humans.'" (BBC NEWS, 2006).

In a lighter vein, the red deer stag with the great rack of antlers that is associated in many people's minds with the Hartford Insurance Company is one of the most widely reconized symbols in the world of advertizing. This stag is based on the painting "Monarch at the Glen" (dated 1851) by the famous English painter and sculptor Sir Edwin Landseer (1802-1873). Although the Hartford company's use of the stag dates to 1861, the background of the original painting was modified at least two times before 1875 when it was resolved to the one that is used today. This symbol, by the way, probably gained its largest audience when, during the 1970s, the stag was so-to-speak incarnated by Lawrence, an elk that was dubbed "the Hartford stag"; Lawrence wandered around through all sorts of settings as the foci of of television commercials for the company. (see Barlow, 2006)

For those interested in the history of the use of bone, several interesting anecdotes and illustrations (black and white photographs), I recommend two references: Ritchie (1975) and MacGregor (1985).

SIMULANTS: Particularly for collectors of ancient bone tools (etc.), bones with shapes such as those of the "Pseudo-tools made by hyaena digestive juices and gnawing" (Halstead & Middleton, 1972, p.57), though not simulants, seem worth mentioning. True simulants follow:

Ivory - This is a case where ivory pieces have been misidentified, NOT purposely misrepresented as bone, which is be ridiculous. - [Textures marked by differences in distributions of color patterns suffice to distinguish ivory from bone - see descriptions of each.].

***Plastics - Plastics, otherwise unidentified (at least so far as I have been able to determine), have been used for such things as jack-knife casings that resemble bone. - [Close examination suffices because the plastic lacks Haversian canals and other characteristic textures of bone.].

***Resins - Handles of Gaelic sgian dubh ("black dagger") have been made of resin. - [Close examination suffices.].

***Reconstituted bone - Finely powdered bone that has been sintered has been used, usually molded, to fashion figurines etc., but -- I suspect -- usually to resemble ivory rather than bone. - [Close examination suffices.].

REPLICAS: Many replicas of animals, including humans, have been produced for such diverse things as teaching aids and ostentatious displays. Most are made from resin plus or minus additives such as crushed bone; some are subsequently weathered before being marketed. One of the finest replicas I have seen was a collection piece hunter's knife with a ceramic handle featuring a stag with a ten-point rack and its doe mate. Some so-to-speak replicas -- most are what I would characterize as cartoon-like moose with full racks -- have been made for use as Christmas tree ornaments, footrests, mantel pieces for holiday festivities and slippers. Rather life-like Bas-reliefs of elks are featured on many ceramic steins and also on some rather interesting jewelry boxes -- interesting because the material from which they are made, called "incolay stone," is described in advertisements as a "complex combination of ... [apparently crushed and sintered] quartz, onyx and carnelian." Essentially two-dimensional representatives of these same animals are also marketed: Examples are engraved glass steins, flat metal wall hangings, pillow covers and clothing (e.g., nightshirts and T-shirts).

R.V. Dietrich © 2016

Last update:

22 June 2016

web

page created by Emmett Mason